By Christopher Klein

✅ AI Essay Writer ✅ AI Detector ✅ Plagchecker ✅ Paraphraser

✅ Summarizer ✅ Citation Generator

A dense ocean of humanity lapped up to the doorstep of John L. Sullivan’s gilded liquor palace. Heads craned and tilted as hordes of Bostonians attempted to steal a passing glance of their hometown hero through the open doorway. Inside, a ceaseless flow of well-wishers offered their farewells to America’s reigning heavyweight boxing champion.

A dense ocean of humanity lapped up to the doorstep of John L. Sullivan’s gilded liquor palace. Heads craned and tilted as hordes of Bostonians attempted to steal a passing glance of their hometown hero through the open doorway. Inside, a ceaseless flow of well-wishers offered their farewells to America’s reigning heavyweight boxing champion.

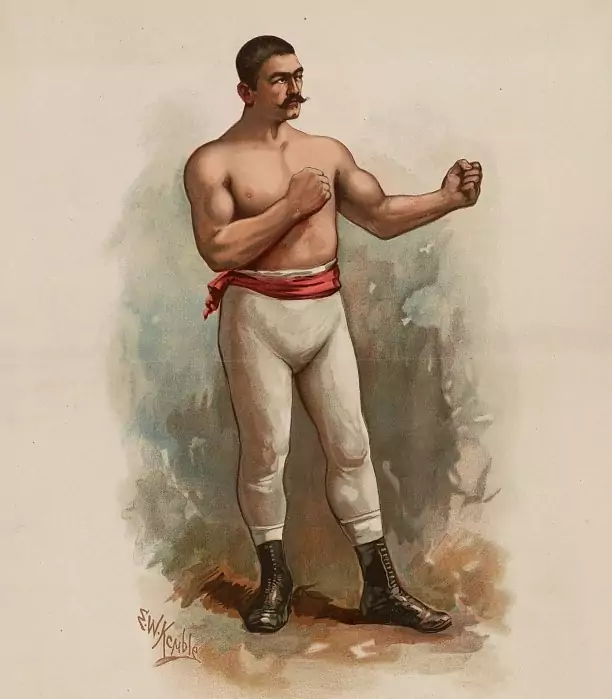

Sullivan’s dark, piercing eyes gleamed with the reflections of the flickering gaslights. His clean-shaven chin glistened like polished granite, although darkness hid in the recesses of a deep dimple and in the shadow of his glorious handlebar mustache. Sullivan’s pristine skin, full set of even teeth, and straight nose belied his profession and visibly testified to the inability of foes to lay a licking on him. Muscular without being muscle-bound, the “Boston Strong Boy” was constructed like a pugilistic product of the Industrial Age, a “wonderful engine of destruction” manifest in flesh and blood.

After imbibing the adulation inside his saloon on the evening of September 26, 1883, the hard-hitting, hard-drinking Sullivan waded through the throng of fawning fans outside and stepped into a waiting carriage that sprinted him away to a waiting train. The man who had captured the heavyweight championship nineteen months prior had departed on many journeys before, but no man had ever set out on such an ambitious adventure as the one he was about to undertake.

For the next eight months, Sullivan would circle the United States with a troupe of the world’s top professional fighters. In nearly 150 locales, John L. would spar with his fellow pugilists, but also present a sensational novelty act worthy of his contemporary, the showman P. T. Barnum. The reigning heavyweight champion would offer as much as $1,000 ($24,000 in today’s dollars when chained to the Consumer Price Index) to any man who could enter the ring with him and simply remain standing after four three-minute rounds.

The “Great John L.” was challenging America to a fight.

Sullivan’s transcontinental “knocking out” tour was gloriously American in its audacity and concept. Its democratic appeal was undeniable: any amateur could take a shot at glory by taking a punch from the best fighter in the world. Furthermore, the challenge, given its implicit braggadocio that defeating John L. in four rounds was a universal improbability, was an extraordinary statement of supreme self-confidence from a twenty-four-year-old who supposedly bellowed his own declaration of independence: “My name is John L. Sullivan, and I can lick any son-of-a-bitch alive!”

The “knocking out” tour opened in Baltimore on September 28 before thirty-five-hundred eager fight fans who filled Kernan’s Theatre. No audience member challenged Sullivan on opening night, but a “flutter of excitement” palpitated through the boxing “fancy” when the champion donned gloves to spar with the constellation of boxing’s brightest stars who comprised the “Great John L. Sullivan Combination.”

After opening night, it was onto Virginia and Pennsylvania. The locales started to blur by—Harrisburg, Scranton, Lancaster.

John L. finally encountered his first challenger in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Local slugger James McCoy looked like the consummate tough guy. Tattoos of snakes, flowers, and a wide-mouthed dragon plastered his broad chest. The 160-pounder’s looks proved deceiving, however. After McCoy opened with a weak blow, the champion needed only a right and a left. The fight was over in mere seconds. “I never thought any man could hit as hard as he does,” McCoy said afterward. “But I can say what few men can, that I fought with the champion of the world.”

And that is precisely why the “knocking out” tour generated unprecedented publicity in newspapers around the country, both for Sullivan and the entire sport of boxing. Not only was the best fighter in the world bringing the sport to the masses, he was letting the masses get in the ring with him!

Youngstown. Steubenville. Terre Haute.

In Chicago, the crowds were so thick that the Combination pulled in nearly $20,000 in two nights. In St. Paul, Minnesota, Sullivan finally faced an opponent who could match him pound for pound. As soon as time was called, Sullivan stretched out his arm, and six-foot-tall railroad engineer Morris Hefey, who weighed 195 pounds, “fell on the stage as if struck by an axe.” The challenger rose, but as soon as he was within arm’s reach of the champion, he was down again. The fight took thirty seconds. “If you want to know what it is to be struck by lightning,” the challenger said afterward, “just face Sullivan one second.”

McGregor. Dubuque. Clinton.

In Davenport, blacksmith Mike Sheehan, the “strongest man in Iowa,” told his family that he was going to face off with the champion. Sheehan’s frantic wife visited Sullivan before the fight and beseeched him not to fight her husband, but not for the reason the champion suspected. “We’ve got five small children, and I don’t want them to have a murderer for a father. If you get into a fight with him, he’ll surely kill you,” she warned the champion.

John L. took his chances, entered the ring, and started with a smash to the nose of the stunned challenger. Sheehan’s surprise turned to rage. He charged at Sullivan. A big clout on the jaw by the champion sent his foe spinning to the back of the stage, and the challenger decided he had taken enough punishment. Sullivan sent Sheehan away with $100 for being game.

Muscatine. Omaha. Topeka.

As the Combination rattled into Colorado at Christmastime, their train ascended the Rocky Mountains. Sullivan’s unprecedented transcontinental tour and his traverse of the West would not have been possible without one of the technological marvels of the age: the railroad. Only fourteen years had slipped by since the driving of the Golden Spike married the Union Pacific to the Central Pacific and bonded the nation’s railway system together. In the decade between 1870 and 1880, railway mileage in the United States almost doubled from nearly fifty thousand to over eighty-seven thousand. In the West, however, mileage more than tripled.

The railroads were powerful symbols of the industrial might of Gilded Age America. “The old nations of the earth creep on at a snail’s pace; the Republic thunders past with the rush of the express,” wrote steel magnate Andrew Carnegie of the raw energy that stoked the United States in the 1880s. That same rough fire of youth burned inside Sullivan and propelled him like a “living locomotive going at full speed.”

In fact, perhaps no American has so embodied his times like John L. The United States was the fastest-growing country in the world. Its population would soon eclipse that of Great Britain, and it was on its way to becoming the world’s leading industrial superpower. The country pulsated with the infusion of new immigrants, new industry, and new inventions—telephones, electric lights—that were transforming daily life.

Both Sullivan, son of Irish immigrants, and the upstart United States in the 1880s, were young and virile, proud, cocky, crude, and pugnacious. A boxer represents power in its most visceral sense, and John L. symbolized an ascendant America that was flexing its economic muscles on the world stage. The champion exuded a rough masculinity that appealed to the growing numbers who feared that life in an increasingly-urbanized United States was becoming less rugged, more sedentary. And at a time when the increasingly popular theory of social Darwinism emphasized the survival of the fittest, there was no place in America where that could be so clearly demonstrated than inside a boxing ring.

The legendary spirit of the fighting Irish that was made flesh in Sullivan transformed him into a hero for the sons and daughters of the Emerald Isle who had felt emasculated in the wake of the Great Hunger. To Irish Americans who had believed themselves powerless for centuries under the thumb of the British, slighted in their new homeland, and traumatized by the horrific famine of the 1840s, here came one of their own who exuded strength, who did not lack confidence, and who did not suffer from a lack of pride. His self-belief was an elixir for a people who had suffered from malignant shame.

Working-class Irish Americans thought of the champion as one of them: just another Irish bloke scrapping to earn a living with his hands, and on the “knocking out” tour, Sullivan traveled to the outposts where the Irish labored in twelve, fourteen, and sixteen-hour shifts: mining towns and lumber camps along railroad lines that were built by calloused Celtic hands.

As soon as the “Sullivan’s Sluggers” arrived in the mining boomtowns of the Rockies, the outlaw element of the Wild West seemingly infected the fighters. Reports of drunkenness and brawling appeared with increasing frequency in newspapers and made for great copy. On Christmas Day in Denver, Sullivan almost killed a fellow fighter while playing around with a double-barreled shotgun he was told was unloaded. Two days later in Leadville, a drunken Sullivan swaggered—and staggered—through his performance and backstage hurled a lighted kerosene lamp at another fighter following an argument. In Victoria, British Columbia, he was in “a state of beastly intoxication” and refused to stand for a toast to the health of the city’s namesake, Queen Victoria, explaining that he “hadn’t been brought up to seeing Irishmen drinking to the health of English monarchs.”

The Combination reached the Pacific Ocean in early 1884. After visiting Los Angeles, the fighters turned back toward the East with Sullivan leaving a trail of broken bottles and fighters littered across America.

Tucson. Tombstone. Waco.

When Sullivan arrived in Galveston, Texas, he faced perhaps his toughest foe, an imposing cotton baler named Al Marx who was considered the champion of Texas. The challenger wanted to send an early statement, and just after shaking hands, he nailed Sullivan in the jaw. The Texas giant gained confidence after landing several hard blows on Sullivan in the first two rounds, and he was convinced John L. had met his match.

Sullivan had spent the day drinking, but when he came out in the third round, the “cowboy pugilist” noticed a change in the champion’s eyes. John L. glared “like a wild animal.” Then Sullivan launched an “uppercut that lifted the giant almost off the floor” that was followed by a left smash to the jaw. Marx sank “down like a bag of oats.” Sullivan lifted him up and then cracked him over the footlights and into the orchestra pit, which broke two chairs, three violins, and a bass drum. As the Texan lay unconscious, the tour’s financial manager reached into the gate receipts to scrounge for $24 to pay for the destroyed drum.

Mobile. Savannah. Chattanooga.

In Memphis, bricklayer William Fleming took the stage with the champion. At the opening signal, Sullivan charged. He feinted with his left and struck a blow on the lower part of Fleming’s left jaw that knocked him unconscious for fifteen minutes. Total time of the bout: two seconds. Fleming was lifted over the ropes and helped out of the building to his home. When he came to, he asked, “When do me and Sullivan go on?”

“You’ve been on,” he was told.

“Did I lick him?” the oblivious bricklayer asked.

On May 23, 1884, “Sullivan’s Sluggers” pulled into Toledo, Ohio. Nearly eight months after they had started in Baltimore, the Combination had reached their final stop on an epic barnstorm through twenty-six of the country’s thirty-eight states as well as the territories of Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. In spite of Sullivan’s drunken exploits, the tour had been a success, and somehow, through all the debauchery, everyone in the Combination made it through without any permanent damage. According to some accounts, thirty-nine men had stepped into the ring seeking to go four rounds with the champion. Thirty-nine men failed.

Accounts of the financial receipts from the tour vary, but Sullivan likely pocketed tens of thousands of dollars, and his earnings probably approached or surpassed the $50,000 annual salary earned by President Chester A. Arthur. While the exact size of his financial windfall may not be known, it is certain that Sullivan earned an incredible level of superstardom by traversing the continent. The “Boston Strong Boy” proved to be a drawing card around America due to both his prowess in the ring and his personal magnetism. Americans paid money not just to see John L. Sullivan box, but just to see John L. Sullivan. On Sullivan’s tour stop in St. Louis, five thousand people paid just to see him pitch five lackluster innings in an exhibition game for baseball’s St. Louis Browns.

Thanks to the “knocking out” tour, Sullivan became the most famous athlete in the United States—and one of the most famous Americans in any walk of life. Through railroads and newspapers, Sullivan was able to reach hundreds of thousands of people across America—something that was not possible just years before. He became an American celebrity of the highest order, as well as the first sports superstar, and his fame would endure even after he lost the heavyweight championship to “Gentleman Jim” Corbett in 1892.

The American publicity machine was beginning to crank, and John L. knew how to pull the levers. He rarely turned down a request for an interview, and he was good copy. His boozing, womanizing, and chronic police-blotter presence were godsends to big-city newspapers engaged in heated circulation wars. John L., like generations of athletes to follow, thought that the spotlight pointed at him by the press burned too harshly at times. “My excesses have always been exaggerated,” he said. “I am almost as much in the public eye as the President of the United States.” John L. had it wrong, however. He lived a life much more in the public eye than the president.

The American people wanted a piece of John L. Women purchased his shorn hair from his barber for a dollar to snap into their lockets. Vaudeville songs and marching tunes were written in his honor. “Let me shake the hand that shook the hand of Sullivan” quickly became a cultural catchphrase, and wherever John L. traveled, an outstretched arm always reached in his direction.

Sullivan later pointed to the transcontinental “knocking out” tour as the seminal moment in his lofty career. “I have always believed what popularity I have today is due to that triumphal tour,” he said after his fighting days were done. It was a logistical endeavor, however, that would not have even been technologically possible a decade before.

Newly-constructed railroad lines allowed Sullivan to cover enormous swathes of America, from frontier settlements to major metropolitan areas, in short order. He could be in Rawlins, Wyoming, one night and nearly three hundred miles away in Salt Lake City the next. The ability to traverse hundreds of miles on a single overnight train made it possible for legions of his fans to view him in the flesh, to be personally awed by his ring prowess, and seduced by his charisma. Sullivan became one of the most “seen” men in the world. Certainly, more eyes gazed upon him than even the president of the United States, and the audiences he drew around the country rivaled those of Barnum and “Buffalo Bill.”

It was the simultaneous communications revolution, however, that allowed Sullivan to connect with exponentially more Americans than just those who saw him in person. The subterranean printing presses that rumbled beneath the streets of the country’s big cities were in the process of shaking up American culture. Print barons such as Joseph Pulitzer and Charles A. Dana noted the success of tabloids such as The National Police Gazette in pioneering sports coverage, and they followed suit by hiring sporting editors and developing their own sports sections.

Some of the big cities that Sullivan visited supported a half-dozen daily newspapers or more, and John L. spawned page-one headlines wherever he traveled. Thanks to brand-new telegraph lines, blow-by-blow accounts of his fights and news of his out-of-the-ring exploits could be transmitted rapidly around the country, which meant that oceans of ink were spilled on him every day. With every story about Sullivan that coursed through the tentacles of America’s telegraph lines, his fame and celebrity deepened.

The intense press coverage and fan interest surrounding the “knocking out” tour provided a mere glimpse of the future. With a transportation and communications network stitching the country together and a burgeoning mass media, the modern sports age had begun, and in John L. Sullivan it had found its first athletic god.

Source: The Public Domain Review

This article was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: http://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Reference

- Life and Reminiscences of a 19th Century Gladiator (1892) by John L. Sullivan

- Internet Archive

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.