In October of 1856, readers of the New York Daily Times were eager for news from Siam. In the 1850s, most Americans would only be familiar with the southeast Asian nation now known as Thailand through its most famous citizens, Chang and Eng Bunker, the original “Siamese twins,” who had been living in the U.S. since 1830. But the Kingdom of Siam itself—its geography, its government, its culture—was a total mystery. However, a new treaty between Siam and the United States, negotiated in 1856 by Townsend Harris, the first U.S. Consul General in Japan, kindled a public interest in all things Siamese. In an article titled “From Siam,” the Times’ correspondent did not hesitate to dampen the public’s enthusiasm. “The importance of a commercial treaty with such a people has been and will be overrated in the United States,” he writes. “The present prospects of Siam are not flattering.” Seemingly without any sense of irony, the author of “From Siam” criticized the widespread practice of slavery in Siam, and stated his belief that “The kingdom is in a state of unrest… which may end in a civil war.”

In October of 1856, readers of the New York Daily Times were eager for news from Siam. In the 1850s, most Americans would only be familiar with the southeast Asian nation now known as Thailand through its most famous citizens, Chang and Eng Bunker, the original “Siamese twins,” who had been living in the U.S. since 1830. But the Kingdom of Siam itself—its geography, its government, its culture—was a total mystery. However, a new treaty between Siam and the United States, negotiated in 1856 by Townsend Harris, the first U.S. Consul General in Japan, kindled a public interest in all things Siamese. In an article titled “From Siam,” the Times’ correspondent did not hesitate to dampen the public’s enthusiasm. “The importance of a commercial treaty with such a people has been and will be overrated in the United States,” he writes. “The present prospects of Siam are not flattering.” Seemingly without any sense of irony, the author of “From Siam” criticized the widespread practice of slavery in Siam, and stated his belief that “The kingdom is in a state of unrest… which may end in a civil war.”

✅ AI Essay Writer ✅ AI Detector ✅ Plagchecker ✅ Paraphraser

✅ Summarizer ✅ Citation Generator

If the Times’ correspondent failed to see the shared potential for civil unrest in both his own country and Siam, other points of comparison between Siam and the U.S. were harder to ignore. The author reported that:

…we had a Siamese Prince to visit our ship a short time since, who went by the proud name of ‘Prince GEORGE WASHINGTON.’ During George’s rambles around the ship, if any of his inferior subjects came in his way, they would sprawl themselves out instanter far down and wriggle themselves out of the way like a worm.

A Siamese prince, demanding that his “inferior subjects” prostrate themselves before him, and adopting the name of the United States’ first President, was too odd a figure to ignore; indeed, descriptions of Prince George Washington would become a regular feature of American writing about Siam from the mid-1850s to the turn of the century. But who was this unusually-named prince? And what did the Americans who wrote and read about him think he could teach them about Siam? Or about America?

Prince George Washington was really Prince Wichaichan, the son of the Second King of Siam. The institution of the “Second King” was another common point of confusion for American and European visitors to Siam. The Times’ correspondent attempted to explain the position to his readers using an American political vocabulary: “The second King is a King only in name, being subservient to the first King in all things, and during the life of the first King he is a mere cipher in state affairs, except in his absence, when he holds the reins of government, being a kind of Vice-President.” Perhaps needless to say, the job of the Second King had very little in common with the Vice Presidency of the United States. When he came to power in 1851, King Mongkut created the role in order to appease his powerful younger brother, Pinklao. Although the position was largely symbolic, the title would have enhanced Pinklao’s claim to the throne in the event that he outlived Mongkut (he did not). Later in his life, Wichaichan would serve as Second King to Mongkut’s son Chulalongkorn. So although Wichaichan was an important political figure in Siam, he also always kept at a firm remove from a real position of power. He would often meet with visiting U.S. dignitaries, who could not help noting—implicitly and explicitly—the contrast between the nickname “George Washington,” which was synonymous with U.S. political power, and Wichaichan’s seemingly neutered political ambitions.

Wichaichan’s unusual nickname was the result of his father’s commitment to “modernize” Siam by studying and deliberately emulating western culture. This “Siamese Occidentalism,” as the Thai anthropologist Pattana Kitiarsa explained it, “is not simply a reversal of Western Orientalist logics and power/knowledge relations. It is the historically and culturally rooted system of epistemological tactics employed by Siam’s rulers and intellectual elites to turn the Otherness of farang [white foreigners] into ambiguous objects of those elites’ desires to be modern and civilized.”1 Prince George Washington was one such “ambiguous object,” bearing both the name of a U.S. President and a royal title that was wholly incompatible with the American political system. By naming his son Prince George Washington (in addition to his many other royal names and titles), Pinklao wished to communicate that he was a progressive person who was drawn to modern American culture, while never abandoning his fundamental commitment to Siam’s absolute monarchy.

Pinklao’s self-fashioned hybridity was picked up on by visiting American writers, who almost always preferred him to the more conservative and conventional King Mongkut. For example, in his 1873 travelogue Siam, the Land of the White Elephant, as It Was and Is, George B. Bacon recalls a meeting with Pinklao in the year 1857. “It was hard to believe that I was in a remote and almost unknown corner of the old world, and not in the new,” Bacon writes of his visit with the Second King, since “the conversation was such as might take place between two gentlemen in a New York parlor.” For Bacon, even Pinklao’s clothing becomes a metaphor for the Second King’s Siamese-American hybridity and the transformation Siam itself will undergo as a result of its increased contact with the West. “Half European, half Oriental in his dress, he had combined the two styles with more good taste than one could have expected,” Bacon writes. “It was characteristic of that transition from barbarism to civilization, upon which his kingdom is just entering.”

If an American writer like Bacon could view Pinklao’s clothing as a metaphor for Siam’s social transformation, then the Second King’s son, Prince George Washington, was an even more potent political symbol. There is some disagreement about whether Pinklao named Wichaichan “George Washington” himself, or if it was the work of a patriotic American missionary. In The English Governess at the Siamese Court, Anna Leonowens claims that “an American missionary, who was on terms of intimacy with the father, named the child ‘George Washington,”‘ and in an obituary for Wichaichan printed in the Baptist Missionary Magazine, author and missionary Fannie Roper Feudge claims that she “had the honor of naming the royal babe… and as the father had requested that the name selected should combine that of an English king and an American president, ‘George Washington’ was chosen.” It is unlikely that Wichaichan would have been given this nickname without his father’s explicit approval, but it is possible that Feudge or another American missionary may have suggested Washington as a suitable name for the young Siamese prince. If this is the case, it would be consistent with how American writers in the nineteenth century used the iconic image of George Washington to think about the United States’ increasing contact with exotic and distant lands and peoples. Because he was such a definitive and recognizable symbol of the United States itself, Washington was the perfect figure for expressing concern over what might happen to the American character if it came into contact with a foreign “other.”

Early in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby Dick, Ishmael struggles to reconcile his conflicted feelings for the South Seas harpooner Queequeg. At first, Ishmael is worried that Queequeg is a cannibal who will murder him in his sleep, but after they share a bed for the night, Queequeg declares that he and Ishmael are “married… meaning, in his country’s phrase, that [they] were bosom friends.” Queequeg’s otherness is offset by his sudden and profound intimacy with Ishmael—the cannibal from Kokovoko is now part of Ishmael’s American family. Fascinated by his new friend, Ishmael offers the following odd description of Queequeg:

With much interest I sat watching him. Savage though he was, and hideously marred about the face—at least to my taste—his countenance yet had a something in it which was by no means disagreeable. You cannot hide the soul. Through all his unearthly tattooings, I thought I saw the traces of a simple honest heart; and in his large, deep eyes, fiery black and bold, there seemed tokens of a spirit that would dare a thousand devils. And besides all this, there was a certain lofty bearing about the Pagan, which even his uncouthness could not altogether maim. He looked like a man who had never cringed and never had had a creditor. Whether it was, too, that his head being shaved, his forehead was drawn out in freer and brighter relief, and looked more expansive than it otherwise would, this I will not venture to decide; but certain it was his head was phrenologically an excellent one. It may seem ridiculous, but it reminded me of General Washington’s head, as seen in the popular busts of him. It had the same long regularly graded retreating slope from above the brows, which were likewise very projecting, like two long promontories thickly wooded on top. Queequeg was George Washington cannibalistically developed.

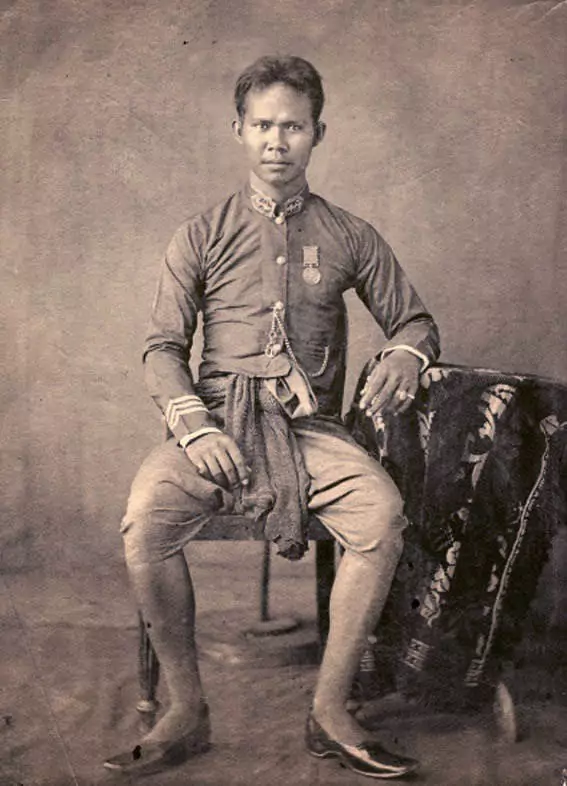

Ishmael was not alone in his phrenological fascination with George Washington. In Orson Squire Fowler’s The Practical Phrenologist, Washington is presented as an example of the “well-balanced temperament,” which is “by far the best” skull type Fowler identifies. Queequeg may be “cannibalistically developed,” but his Washington-like phrenological features suggest that he is nevertheless an honest and respectable person. This interest in the features of the original George Washington’s skull can be detected in descriptions of Prince George Washington as well. In Feudge’s obituary for Wichaichan, she notes that “in person, ‘King George Washington’ was of tall, compact figure, indicative alike of strength and beauty; of full, pleasing face, and well-formed head.”

Radicalized George Washingtons were a recurrent trope in nineteenth-century American writing, including in texts set in the United States itself. In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, we are told that “the wall over the fireplace” of Tom’s slave cabin “was adorned with some very brilliant scriptural prints, and a portrait of General Washington, drawn and colored in a manner which would certainly have astonished that hero, if ever he happened to meet with its like.” This portrait of a black George Washington had a real-life analog in Hawaii, at least according to Mark Twain in an 1866 letter written during a visit to the islands (which were not yet part of the U.S.). “We were next introduced to General George Washington,” Twain writes, “or, at least, to an aged, limping Negro man, who called himself by that honored name.” After going on to tell us that this man is kept in chains in a Hawaiian prison, Twain dryly notes, “I do not think he is the old original General W.”

For literary critic Amy Kaplan, Twain’s black General George Washington and Melville’s cannibalistic George Washington both serve to “acknowledge and ridicule the desire for independence by non-white peoples”.2 Washington’s image, associated with the Revolutionary War and American liberty, is attenuated by his black skin or tattoos, creating a juxtaposition that would be amusing to white nineteenth-century readers who were skeptical that the freedoms Washington stood for could be extended to non-white persons as well. A similar dynamic is at work in descriptions of Prince George Washington, as American writers wanted to acknowledge and approve of attempts by Siamese elites like Pinklao, Wichaichan, and Chulalongkorn to “modernize” Siam by becoming more American, while also maintaining a strict distinction between the non-white Siamese and white Americans.

In his recollection of his visit with Pinklao in 1857, George B. Bacon also shares his impressions of Wichaichan. Bacon is pleased with the physical appearance of the “tall, manly, handsome youth” when he meets him, but is even more taken aback by his unusual name:

He has a kingly name—a more than kingly name. For the second king, seeking a significant name for his son, chose one which had been borne, not by an Asiatic, not by a European, but by the greatest of Americans—George Washington. ‘What’s in a name?’ It may provoke a smile at first, that such a use should be made of the name Washington, as if it were the whim of an ignorant and half-savage king. But when it shall appear, as I shall make it appear before I have finished, that this Siamese king understood and appreciated the great character of the man after whom he wished his son to be called, I think that no American will be content with laughing at him. I own that it moved me with something more than merely patriotic pride to hear the name of Washington honored in the remotest corner of the old world.

Bacon’s optimism is qualified, however, when he and Prince George Washington walk together toward the Second King’s palace. “I suddenly missed the young man from my side, and turned to look for him,” Bacon writes:

What change had come over him! The man had been transformed into a reptile. The tall and graceful youth, princely in look and bearing, was down on all his marrow-bones, bending his head until it almost touched the pavement of the portico, and, crawling slowly toward the door, conducted me with reverent signs and whispers toward the king, his father, whom I saw coming to meet us.

For Bacon, this contrast between the handsome, modern Prince named after “the greatest of Americans” and the absolute obeisance demanded by the Siamese monarchy is “characteristic of the strange conflict between the old barbarism and the new enlightenment which one meets at every turn” in Siam. Like the radicalized George Washingtons described by Melville, Stowe, and Twain, this George Washington stops short of attaining the grandeur of his American namesake. This point is brought home for Bacon during his lunch with the Second King, as he imagines that “the portrait of the real George Washington on the wall” of Pinklao’s palace would “blush with shame and indignation” if “it looked down on the reptile attitude of his namesake.” Although the Washington portrait is merely a representation of the real George Washington, it is seemingly a more faithful copy of the original than the Siamese prince lying prostrate on his father’s floor.

Although Wichaichan would succeed his father as Second King, his political career did not have a happy ending. In 1875, when his cousin First King Chulalongkorn tried to introduce progressive reforms to the Siamese political system, the conservative Wichaichan attempted to seize power. When this failed, he sought shelter with the British Consulate, eventually negotiating a truce with Chulalongkorn that allowed him to return to his palace, but with a reduced personal guard and limited political influence.

Unlike General Washington, Prince George Washington had failed to lead a political revolution. Descriptions of Wichaichan following the “Front Palace Crisis” typically represent him as a somewhat sad, frustrated old man (even though he was only in his early 40s). A striking example can be found in John Russell Young’s Around the World with General Grant, a travelogue that recounts Ulysses S. Grant’s world tour following his second term as President of the United States. Like George Washington, Grant was a President who earned his political capital through his storied military career. And so, in a odd way, the meeting between Ulysses S. Grant and Prince George Washington was an anachronistic encounter between two of America’s most celebrated heroes. And yet, of course, the contrast between Prince George Washington and the real General Washington was too great for Grant—and Young, his biographer—to ignore. Young describes he and Grant waiting for Wichaichan in his palace, which to their eyes “bore an aspect of decay.” “In a few moments, his Majesty appeared and gave us a cordial greeting,” Young writes:

An illness in his limbs gives him a slow, shuffling gait, and he told us he had not been in the upper story of his palace for a year. We sat under the canopy and talked about only America and Siam. No allusion was made to any political question, the King saying that he gave most of his time to science and study. Having a nominal authority in the State, he has time enough for the most abstruse calculations. Deprived of any real power, Prince George Washington—now King George Washington—lives in a dilapidated palace and pursues harmless intellectual pursuits instead of the political duties that his royal birth and famous name should have prepared him for.

“The King seemed sad and tired in his manner,” Young writes, “as if he would like really to be employed, as if he felt that when one is a king he should be at more stable occupations than turning ivory boxes on a wheel, or mixing potter’s clay.” When the real George Washington retired to his slave plantation at Mount Vernon, he was regarded as a hero in the United States and throughout the world. The contrast between Washington’s retirement, resting on the laurels of a lifetime of military and political victories, and the forced retirement of Siam’s King George Washington is palpable in Young’s description, as a former U.S. President looks with pity on a radicalized and debased copy of one of America’s founding fathers.

From the first time he was noticed by the New York Daily Times in 1856, until his death in 1885, Wichaichan would always be interpreted through the lens of his American nickname. Being named “George Washington” suggested that he was a new kind of Siamese noble, a modern, Americanized monarch who heralded a departure from the old stereotype of the “Oriental despot.” But his—and his father’s—commitment to the conservative conventions of the Siamese monarchy, meant that Prince George Washington would always be kept at an arm’s length from his famous namesake. In his famous book The Location of Culture, Homi K. Bhabha describes “colonial mimicry” as a state of being “almost the same but not quite,” or more pointedly, “almost the same but not white.”3 This formulation encapsulates the attitude American writers had toward Prince George Washington, a sense of admiration and attraction offset by a deep revulsion toward cultural and racial difference. Although they were flattered to see their national hero honored in a foreign land, they believed that this living tribute could never match the original. There may have been two kings in Siam, but American history only had room for one George Washington.

References

- Pattana Kitiarsa, “An Ambiguous Intimacy: Farang as Siamese Occidentalism,” in The Ambiguous Allure of the West, eds. Rachel V. Harrison and Peter A. Jackson (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), 58.

- Amy Kaplan, The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture, Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2005, 86.

- Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, London and New York: Routledge, 2004, 127-128.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.